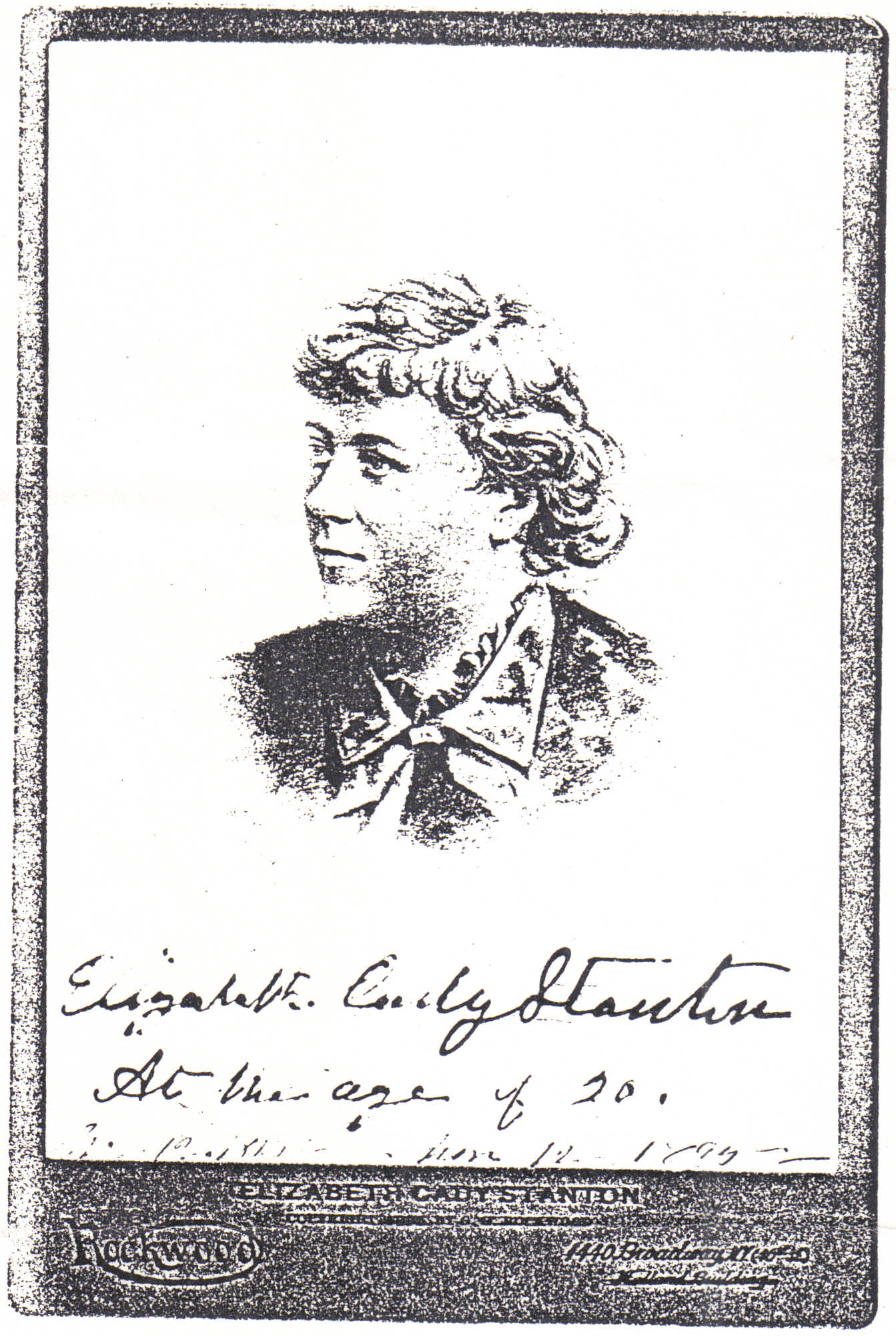

Mrs. Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Suffragist and Feminist

Elizabeth Cady Stanton ignited a rebellion that brought about one of history’s largest revolutions in social change. She was a brilliant writer, strategist and philosopher. At the same time, she was a wife, mother of seven children, and revolutionary.

Recent historians have illuminated Elizabeth Cady Stanton as the leading suffragist and feminist reformer of 19th century America. The rebellion caused Americans to reevaluate laws and customs treating women as dependents of men, without need of, or rights to, the same opportunities.

Our struggle shall be hard and long but our triumphs shall be complete and forever.

Address by Elizabeth Cady Stanton on Women’s Rights, Waterloo, NY.

The Beginning of a bloodless revolution…

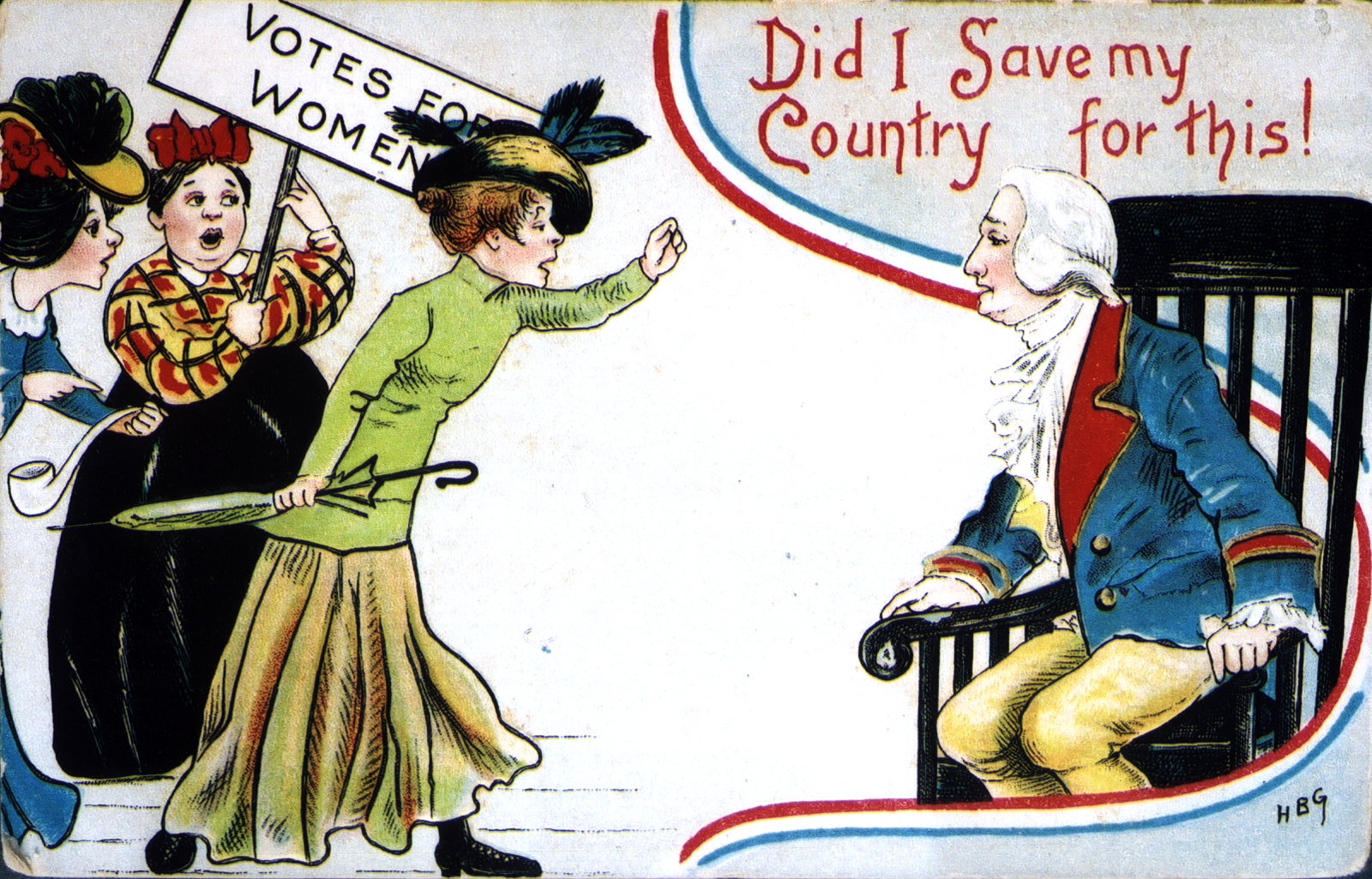

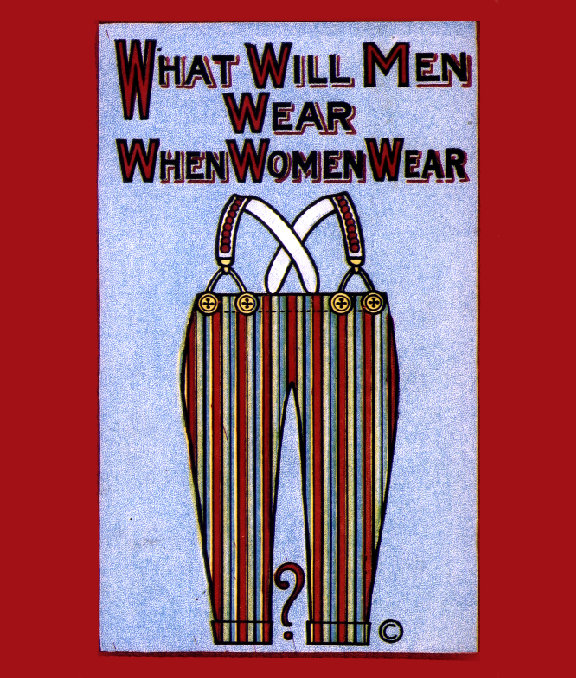

While their way of dress appears prim and awkward by today’s fashion, our activist ancestors were bold and rebellious in their words, expectations, and demand for the right to vote. It was a bloodless revolution, launched in 1848 with the Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, but it would take a 72-year battle culminating in the turbulent passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 for women to finally gain the right to vote.

The Cady home in Johnstown, NY

Oh, My daughter, I wish you were a boy!

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, born November 12, 1815 in Johnstown, New York, was the eighth of ten children. The daughter of well-to-do-parents, her mother Margaret Livingston in 1801 married Daniel Cady who became a state Supreme Court judge. The family’s future was centered around the male heirs; however, four of the five sons died in infancy and by the time she was 11 years old, her only living brother, Eleazar, passed away after graduating from Union College. Her father was devastated. Elizabeth recorded how she tried to comfort him in his grief.

“I still recall …going into a large, darkened parlor to see my brother and finding the casket, mirrors and pictures all draped in white, and my father seated by his side, pale and immovable. As he took no notice of me, after standing a long while, I climbed upon his knee, when he mechanically put his arm about me and with my head resting against his beating heart we both sat in silence, he thinking of the wreck of all his hopes in the loss of a dear son, and I wondering what could be said or done to fill the void in his breast. At length, he heaved a deep sigh and said: ”Oh, my daughter, I wish you were a boy!” Throwing my arms about his neck, I replied: “I will try to be all my brother was.” Elizabeth Cady Stanton, an excerpt from Eighty Years And More: Reminiscences 1815-1897, 1898

“Oh, my daughter, I wish you were a boy!”

Daniel Cady, 1826

Either sex, in isolation, is robbed of one-half its power for the accomplishment of any given work.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, 1895

Two prizes were offered in Greek…How well I remember my joy in receiving that prize. One thought alone filled my mind. “ “Now”, said I,” my father will be satisfied with me.” So as soon as we were dismissed, I ran down the hill, rushed breathless into his office, laid the new Greek Testament which was my prize on his table and exclaimed: “There, I got it!” He took up the book, asked me some questions about the class, the teachers, the spectators, and, evidently pleased, handed it back to me. Then, while I stood looking and waiting for him to say something which would show that he recognized the equality of the daughter with the son, he kissed me on the forehead and exclaimed, with a sigh, “Ah, you should have been a boy!”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, excerpt from Eighty Years And More: Reminiscences 1815–1897, 1898

Youngest known image of Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Created equal

Her father’s attitude affected young Elizabeth deeply, and set the stage for a life dedicated to reversing society’s unfair treatment of women. She foreshadowed her own role as an activist when, as a child going through her father’s law books, she thought of cutting out all passages that prevented women from having rights equal to men. Only, she was caught before she could begin the deed. Her father instructed her, to change a law, one must appeal to legislators who pass laws. Later, in 1854, Elizabeth did just that. She appeared before the New York State legislature, speaking in favor of women’s property rights.

All men are created equal.

Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence, 1776

All men and women are created equal.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton,Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, 1848

To make laws that man cannot, and will not obey, serves to bring all law into contempt.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, from History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1, 1881

Can you imagine living in a country where women:

- are not allowed to speak in public

- cannot vote or hold elective office

- cannot keep the wages they earn

- cannot attend college

- have few property rights –

- have limited opportunities for employment

These were the circumstances under which American women lived in the 1800s; and Elizabeth Cady Stanton- along with many, many more women inspired by her- challenged those conditions fundamentally.

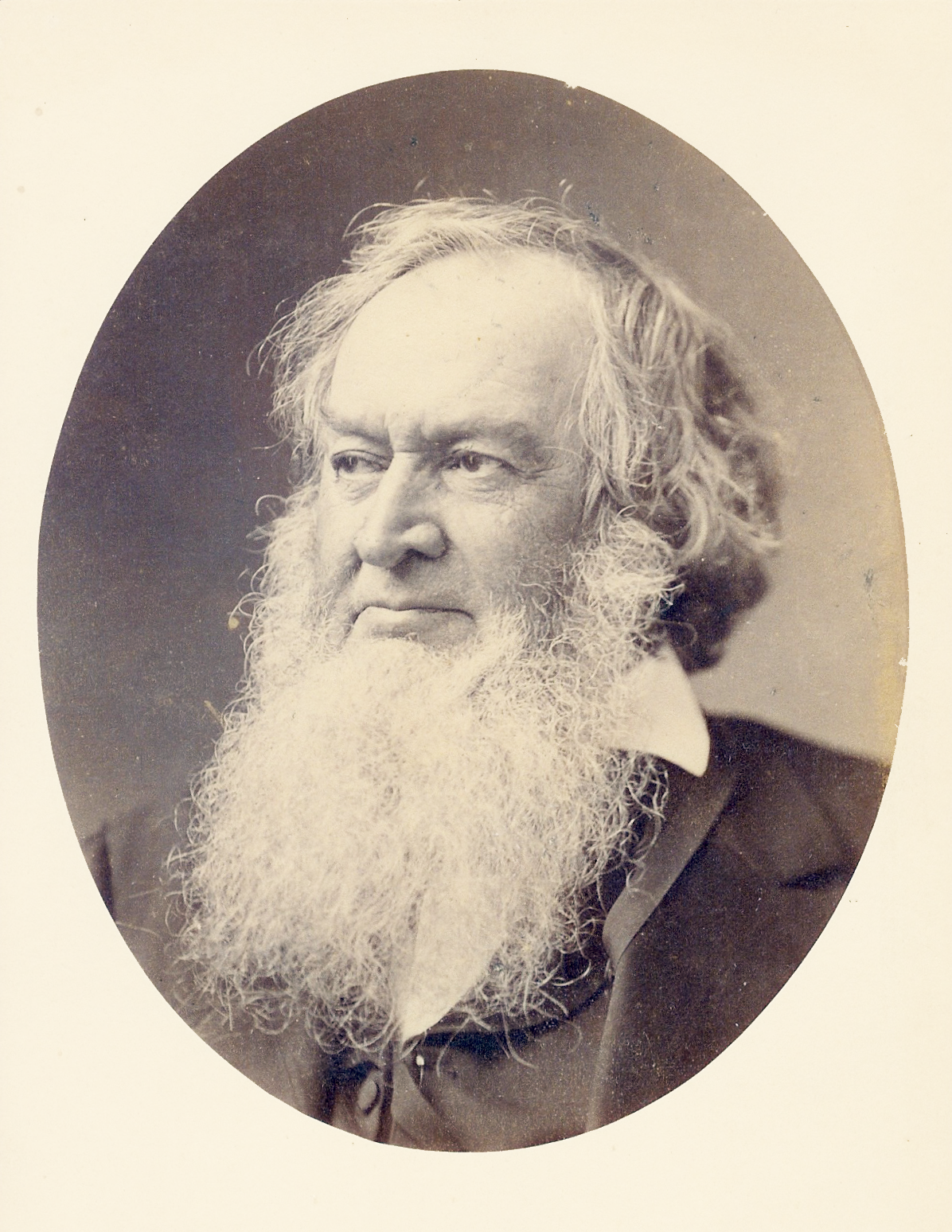

Gerrit Smith

Ready to Make Her Own Rules

Elizabeth wanted to attend college, as was intended for her brothers, but girls were barred from higher education. Smart and energetic, she attended an all-female academy where she was an excellent student, although she thought the rules governing relationships with boys were unfair. By age 18, she had graduated and was ready to forge her own path. She sought the company of high-spirited individuals, especially those involved in abolition and other social reforms of the time. Visiting her cousin Gerrit Smith, she thrived on the excitement of fugitive slaves being harbored in his house and community.

To throw obstacles in the way of a complete education is like putting out the eyes.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, excerpt from Solitude of Self, 1892

Man’s intellectual superiority cannot be questioned until woman has had a fair trial. When we shall have freedom to find our own sphere, when we shall have had our colleges, our professions, our trades, for a century, a comparison then may be justly instituted.

Address by Elizabeth Cady Stanton on Women’s Rights, Waterloo, September, 1848

Freedom to find our own spheres

1830s America was a time of rapid growth and “Jacksonian democracy,” expanding rights and freedoms to all white men. In contrast, the rights and roles of women changed little, having been defined by years of precedent and the social norms. No colleges in the country admitted women. Elizabeth bristled at this. Her father suggested she learn “how to keep house and make puddings and pies.” But the feisty Elizabeth dared to go beyond domestic occupations and household chores. She later wrote, “My vexation and horror knew no bounds.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, excerpt from Eighty Years And More: Reminiscences 1815–1897, 1898

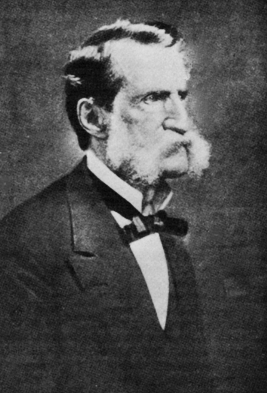

Henry Stanton

A charismatic young woman

Elizabeth Cady was radiant and petite with sparkling eyes and light, curly hair. A charismatic young woman, she enjoyed offering her own opinions. She met her match in the young, handsome, and fiery abolitionist Henry Stanton, and they were married May 10, 1840. Striking the words “to obey” from the traditional wedding ceremony, she started her marriage on level ground, and keeping her maiden name, she was known always, not as Mrs. Henry Stanton, but as Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

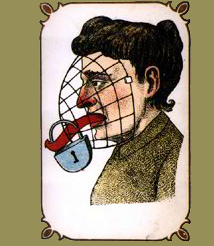

In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Declaration of Sentiments, Seneca Falls Convention, 1848

The World Anti-Slavery Convention, June 12, 1840, in London provided the perfect destination for the young reformists’ honeymoon. But a tremendous stir was caused on the international stage when women delegates were not allowed to speak. The male delegates voted no, saying women’s participation would be “promiscuous.” For Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the convention added to her experiences of being shut out, and served as “the spark that kindled her interest in women’s rights.”

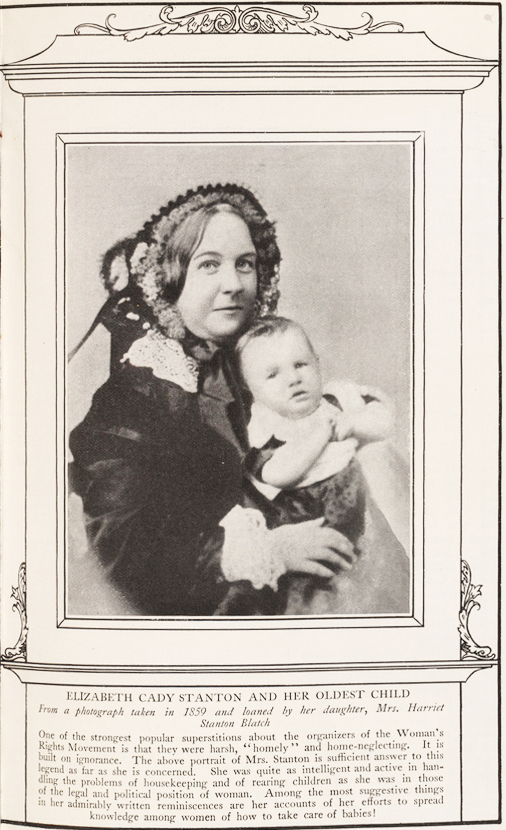

Elizabeth Cady Stanton holding her second daughter, Harriot

A person of ideas

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Henry Stanton moved to Boston where they had three sons. The young Stanton family led a modest but comfortable life. Boston proved to be an engaging environment for Elizabeth, who was a person of ideas. She attended many meetings and lectures, and made friends with the top reformers and intellectuals in the nation, including Nathaniel Hawthorne and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

All sorts of new ideas are seething…

Elizabeth Cady Stanton in a letter to her mother, Margaret Livingston Cady, July, 1845

The prolonged slavery of women is the darkest page in human history.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, from History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1, 1881

Women take note! A mitten that promises a shinier stove. But, for Elizabeth Cady Stanton, an advertisement such as this would only have served as a reminder of the dull, servile responsibilities too often relegated to women.

Lucretia Mott

A Turning Point

As the circumstances of her own personal life unfolded, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was increasingly stirred by empathy with the many other women who were hopelessly shut off from access to the larger world and deprived of rights. In early July of 1848, she accepted an invitation for an afternoon of conversation and tea. Surrounded by women, one of whom was Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth began pouring out her indignation regarding the plight of women.

Lucretia Mott, a prominent Quaker famous for her advocacy of abolition and women’s rights, had met Elizabeth eight years earlier while both were attending the World Anti-Slavery Convention. In 1840, Elizabeth wrote that Mrs. Mott was a new revelation to her, inspiring in her a newborn sense of dignity. In fact, from this earlier meeting and their continued correspondence, Elizabeth learned how the logic of abolishing slavery laid a foundation for enacting women’s rights.

The two friends and relatives wasted no time in bringing to life their desire for a women’s rights convention. This group of five placed a public meeting notice in a local paper. Allowing only a few days to plan, Elizabeth set about drafting The Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, launching the world’s first women’s rights convention on July 19, 1848.

Using the model of the Declaration of Independence, the Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions forthrightly demanded that the rights of women be acknowledged and enacted by society. The lively two-day meeting drew 300 people who identified sources in law and religion that limited women’s sphere. They agreed that the individual rights of women must become part of the fabric of American democracy; they ultimately adopted each resolution for taking action to change customs and laws. The document was signed by sixty-eight women and thirty-two men.

The more complete the despotism, the more smoothly all things move on the surface.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, from History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1, 1881

The silver teaspoon, an instrument of revolution.

In the mid-1800s, the hands that rocked cradles were also stirring tea at parties where women’s rights were the topic of discussion. The more these women talked, the more intensely they stirred their tea, and the more dedicated they became to taking action.

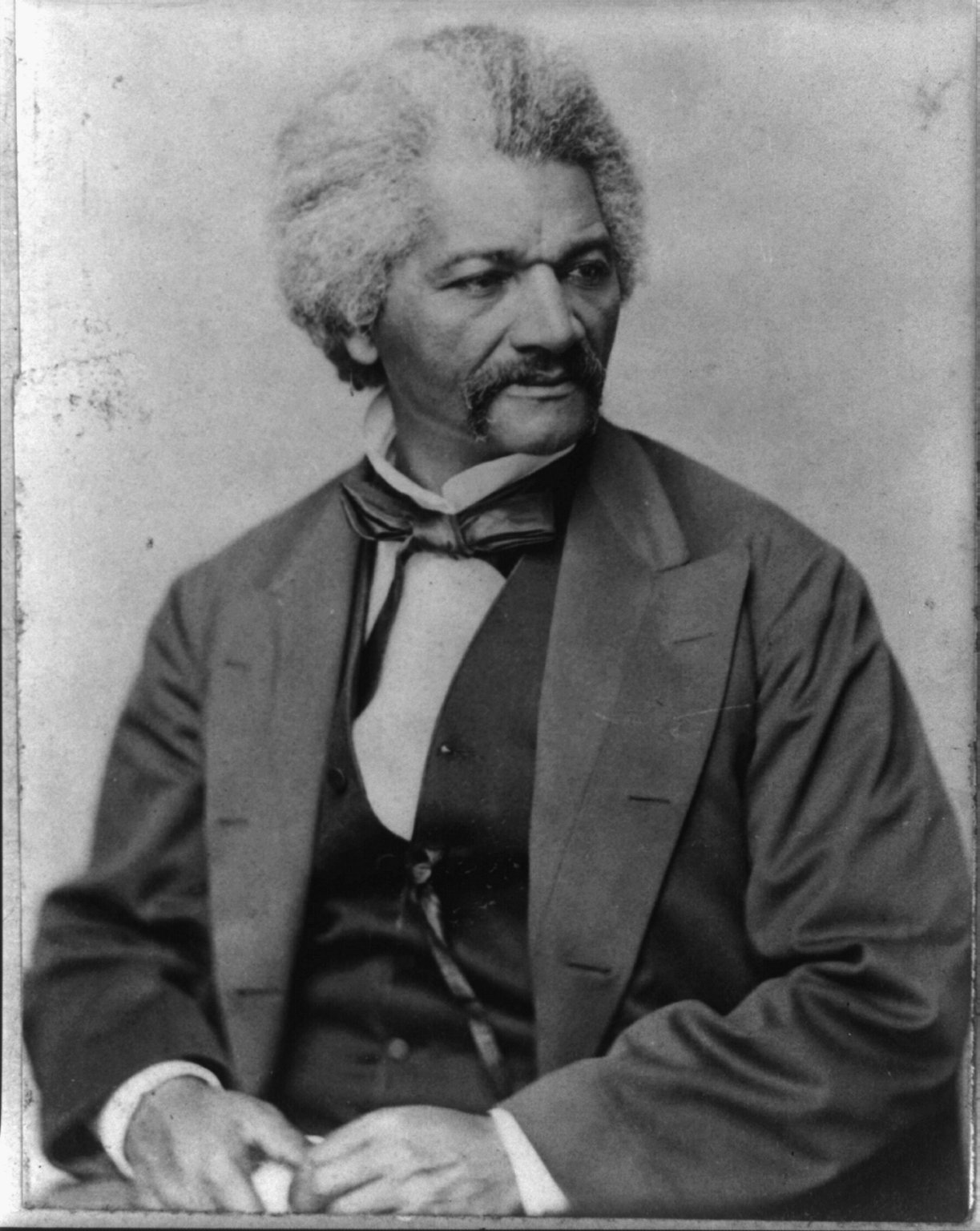

Frederick Douglass

Sparking a revolution

At the convention, the most contentious issue, a woman’s right to vote, was put forth by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. All of her friends and associates, even her husband, told her it was preposterous and ridiculous to have such an unrealistic resolution. But she would not back down, insisting that, “The vote is the right by which all other rights are gained.” She did receive support, however, from the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass, a fellow attendee of the convention, whom she credited with saving the resolution. “…there can be no reason in the world for denying to woman the exercise of the elective franchise, or a hand in making and administering the law of the land,” Douglass wrote.

I feel I am doing an immense amount of good in rousing women to thought and inspiring them with new hope and self respect.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, in a letter to her daughter, Margaret L. Stanton, December 1, 1872

Self-development is a higher duty than self-sacrifice.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, excerpt fromThe Woman’s Bible, 1895

Sojourner Truth delivered her famous speech “Ain’t I A Woman” at the Suffrage Convention held in Akron, Ohio in 1851.

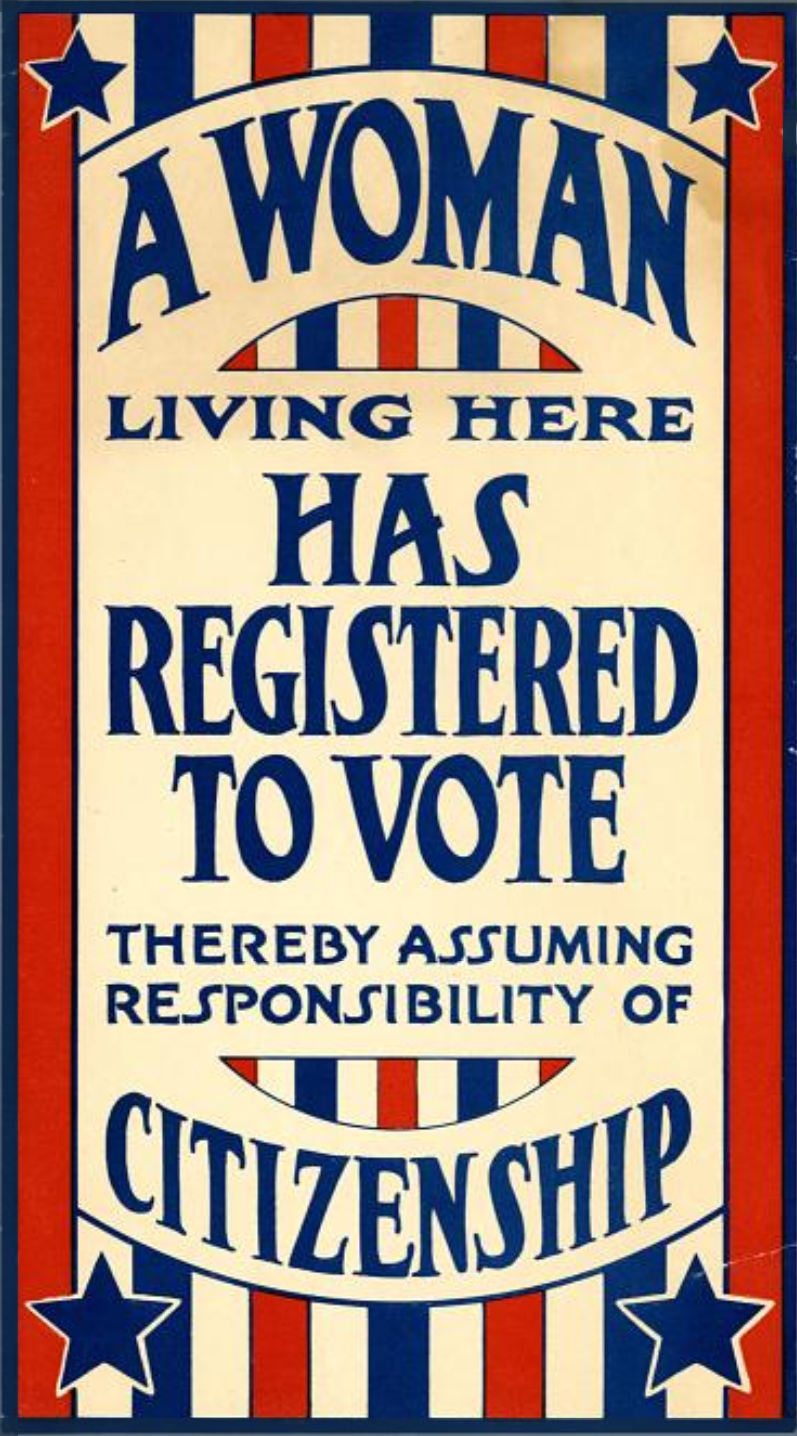

Word of the Seneca Falls convention began to spread throughout New York and other states, and more public meetings were convened where like-minded people deliberated the implications of women’s rights. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her colleagues had sparked a revolution, inspiring women and men all over the country to debate the new ideas, petition for new laws, lobby legislators, hold public meetings, convene conventions, deliver eloquent speeches, and overall push for equal rights for all. Every year after 1848, a Women’s Rights Convention was held until the Civil War intervened.

When Anthony Met Stanton

Bronze statue of the May 1851 introduction of Susan B. Anthony to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Seneca Falls, New York

A momentus meeting...

In May of 1851, Susan B. Anthony was staying at the home of temperance worker Amelia Bloomer, who lived in Seneca Falls. Elizabeth Cady Stanton happened to meet the two women on the street after an anti-slavery meeting, and wrote of the event: “How well I remember the day… Walking home after the adjournment, we met Mrs. Bloomer and Miss Anthony, on the corner of the street, waiting to greet us. There she stood, with her good earnest face and genial smile, dressed in gray delaine, hat and all the same color, relieved with pale blue ribbons, the perfection of neatness and sobriety. I liked her thoroughly. “ Elizabeth Cady Stanton, excerpt from Eighty Years And More: Reminiscences 1815–1897, 1898

While they may not have realized it, this was a pivotal occasion. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony became a formidable partnership, and history continues to recognize them as two of the most powerful and resourceful women of any time. A spark was ignited between them as they became close friends and dynamic colleagues. Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s ability to travel was limited while her children were young. At the same time, Susan B. Anthony, who made the choice not to marry, was tireless in going anywhere, speaking to any group – small or large – about women’s rights, particularly the injustice of women not having the right to vote. As Elizabeth’s family grew, Susan often came to stay with them and cared for the children so Elizabeth could have the time to think, write, and strategize their next move.

… we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton,Declaration of Sentiments, Seneca Falls Convention, 1848

To live for a principle, for the triumph of some reform by which all mankind are to be lifted up to be wedded to an idea may be, after all, the holiest and happiest of marriages.

– Elizabeth Cady Stanton

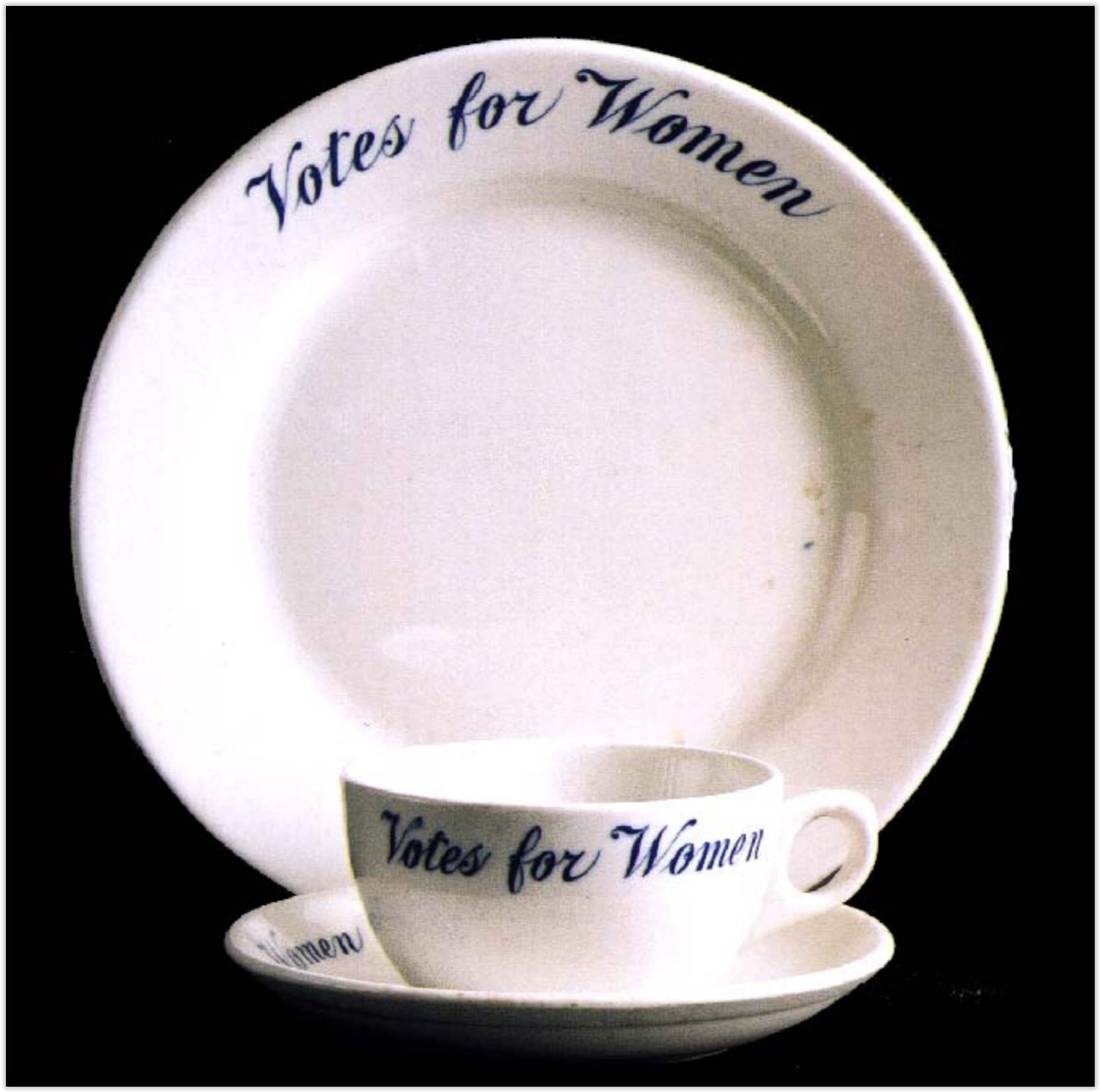

During Mrs. Alva Erksine Smith Vanderbilt Belmont’s divorce from William K. Vanderbilt, grandson of Cornelius, she became acquainted with Anna Howard Shaw, a noted suffragist. Throughout the rest of her life, Alva continued working with and funding the suffrage movement. In 1909, at her home, Marble House in Newport, Rhode Island, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont hosted a women’s suffrage event. This place setting with the “Votes for Women” motto was used for service.

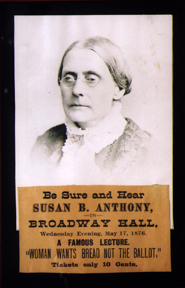

Susan B. Anthony

She forged the thunderbolts and I fired them

Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s compelling speeches and Susan B. Anthony’s forceful delivery, unleashed a revolution that rippled throughout the entire country. They organized women and men to build political power that would change laws and gain the right to vote. Though concentrated in New York State and the northern region before the Civil War, their work shifted its focus to the federal government and amending the United States Constitution at the war’s end. What began as scattered pockets of reformers grew into a national movement. Well into the 20th century, a new generation was energized to carry on the revolution.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton reflected proudly on her relationship with Susan B. Anthony: “In thought and sympathy we are one, and in the division of labor we exactly complemented each other. In writing we did better work than either could alone. While she is slow and analytical in composition, I am rapid and synthetic. I am the better writer, she the better critic. She supplies the facts and statistics, I the philosophy and rhetoric, and, together, we have made arguments that have stood unshaken through the storms of long years–arguments that no one has answered. Our speeches may be considered the united product of our two brains.

In thought and sympathy we are one.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, from History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1, 1881

Our “pathway” is straight to the ballot box, with no variableness nor shadow of turning … We demand suffrage for all the citizens of the republic in the Reconstruction. I would not talk of Negroes or women, but of citizens.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, in letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, January 13, 1868

Sometimes, Susan, I struggle in deep waters.

As ever your friend, sincere and steadfast,

– Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Letter to Susan B. Anthony, July 4, 1858

Elizabeth Cady Stanton with her daughter, Harriot, and her granddaughter, Nora, in 1892.

Not for ourselves alone

Over the next 50 years, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, recognized as national leaders of women, passionately advocated for many fundamental rights, ones that today we take for granted. Women’s rights to:

-

go to college

-

own property in her name

-

keep her earnings

-

end a marriage based on drunkenness, desertion or cruelty

-

share custody of her children

-

be treated as full citizens, not slaves

-

sue in a court of law

-

serve on a jury

-

run for office in public elections

-

serve as President, Senator, Representative and other officials

-

VOTE

Although they met resistance and were often vilified every step of the way, even by other women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were unshaken in their convictions and continued to use the tools of democracy. Once her children were old enough, Elizabeth spent more than 11 years traveling and giving speeches, addressing conventions, legislatures, and federal judicial committees. She was a paid lecturer: witty, brilliant, and charming in converting people to the cause for women. She wrote to her daughter, Margaret, “Above all considerations of loneliness and fatigue, I feel …that I am making the path smoother for you and Hattie and all the other dear girls.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, in a letter to her daughter, Margaret L. Stanton, December 1, 1872

“the most shocking and unnatural event ever recorded in the history of ‘womanity.’”

From an article appearing in the Oneida Whig, August 1, 1848

To deny political equality is to rob the ostracized of all self-respect; of credit in the market place; of recompense in the world of work; of a voice among those who make and administer the law; of a choice in the jury before whom they are tried, and in the judge who decides their punishment.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, excerpt from Solitude of Self, 1892

We think that a man has quite enough to do to find out his own individual calling, without being taxed to find out also where every woman belongs.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, from History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1, 1881

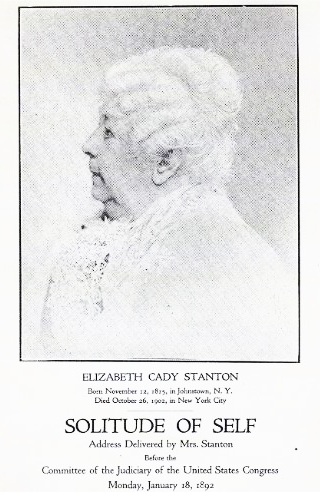

Elizabeth Cady Stanton continued to be a prolific writer, well known for her radical ideas which she shaped into powerful articles and books. She co-authored History of Woman Suffrage, Vols. 1–3; published Eighty Years & More, a memoir, and her most controversial work, The Woman’s Bible. Some of her best writing reveals her sharp eye for injustice to women in courts of law, domestic life, national politics and churches.

In 1892, at age 76, she delivered her ideology in the speech, Solitude of Self, first in written form to the House Committee on the Judiciary of the United States Congress, then in an address to the National American Women Suffrage Association, and two days later, she repeated the speech at a hearing of the Senate Committee on Woman Suffrage. She considered this her best speech and it was later published as a pamphlet. 10,000 copies were printed, placed in envelopes and sent to all parts of the United States by Congress.

The vote is the right by which all other rights are gained.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, from History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1, 1881

“the most shocking and unnatural event ever recorded in the history of ‘womanity.’”

From an article appearing in the Oneida Whig, August 1, 1848

Nothing strengthens the judgment and quickens the conscience like individual responsibility. Nothing adds such dignity to character as the recognition of one’s self-sovereignty; the right to an equal place, every where conceded; a place earned by personal merit, not an artificial attainment, by inheritance, wealth, family, and position.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, excerpt from Solitude of Self, 1892

Knowing she may never see her work become a reality, in 1900, Elizabeth confided in her diary, “We are sowing winter wheat which the coming spring will see sprout and which other hands than ours will reap and enjoy.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, in fact, passed away on October 26, 1902. Eighteen years later, the 19th Amendment was finally ratified, granting women the right to vote. Although she never saw this achievement, she continued to believe that failure was impossible.

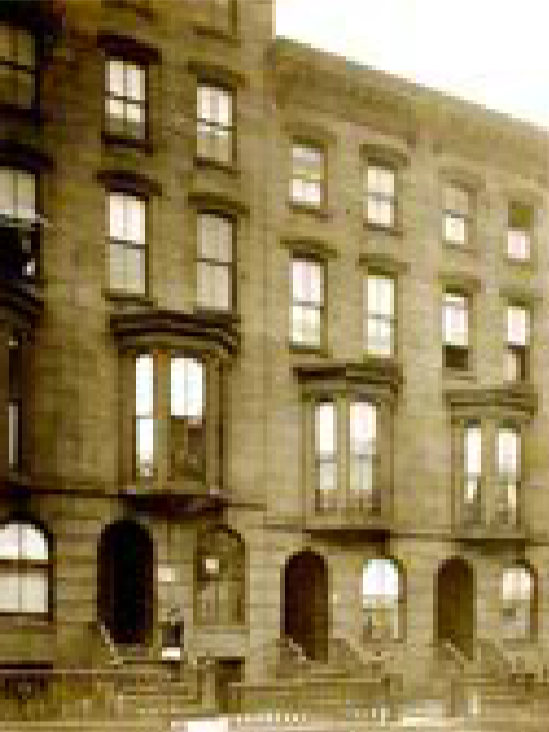

Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s home at 464 West 34th Street in New York City during her candidacy for Congress.

Tools of Democracy

1854 Elizabeth Cady Stanton testifies before the New York legislature demanding equal civil status, including the right to vote, to sit on juries, to equal inheritance, rights of widows, a wife’s right to her own wages, and the revision of the marriage code.

1866 Elizabeth ran for United States Congress as an Independent Candidate.

1868 Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony publish the suffragist newspaper, “The Revolution”, and form the National Woman Suffrage Association.

1876 Elizabeth writes the “Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States” for the U.S. Centennial celebration, 1876.

1878 Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and the women’s rights movement convince Senator Arlen Sargent to introduce what would become, over forty-five years later, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution:

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the US or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have the power, by appropriate legislation, to enforce the provisions of this article.”

1890 Elizabeth is elected President of the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

1895 Elizabeth published The Woman’s Bible. In this work, she and a committee of female theologians criticize established religion’s interpretation of the Bible that clearly promotes the inferiority of women. The National American Woman Suffrage Association votes her out of the organization because of this.

Elizabeth attends her 80th Birthday in the Metropolitan Opera House. The celebration is sponsored by women from all kinds of clubs, societies and professional organizations, not necessarily believing in women suffrage, but recognizing that Stanton had paved their ways.

1902 Elizabeth writes a letter to President Theodore Roosevelt a few days before she dies demanding women’s right to vote and stressing the work of a social movement affecting the rights of half the population- women.

…my creed is free speech, free press, free men, and free trade- the cardinal points of democracy.

An excerpt from Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s appeal to the electors of the Eighth Congressional district, New York, October 10, 1866

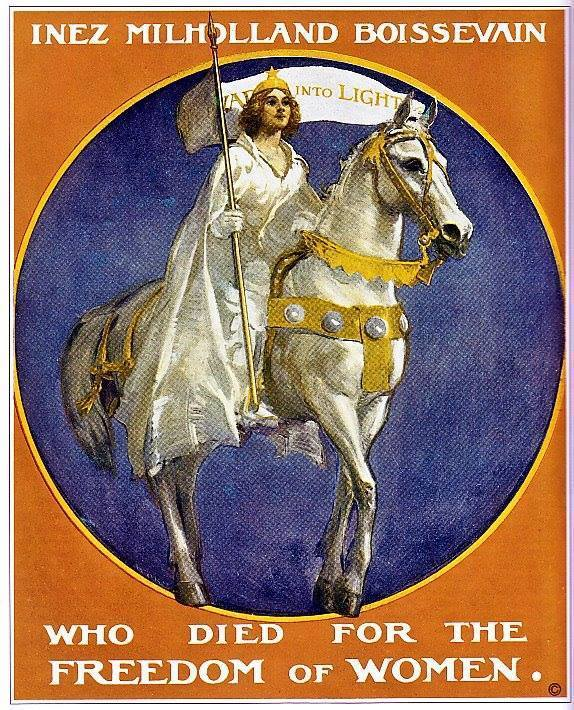

Inspired by the constant campaigning of many women like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a younger generation of suffragists joined the struggle for women’s rights. Depicted in this poster is Inez Milholland Boissevain, draped in white robes and riding a huge white horse while leading a Suffrage Parade in Washington, DC, on March 3, 1913. She was a popular speaker on the campaign circuit of the National Women’s Party in the early 1900s.

Unfortunately, while on a speaking tour, she collapsed, dying ten weeks later at the age of 30. Her last public words were:

“Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?”